At The Movies

Ea

a*k

NAOMI PFEFFERMAN

Special to the Jewish News

tuart Blumberg

remembers the days

when he was a strug-

gling writer, rooming

in New York with his buddy,

Edward Norton, the strug-

gling actor. Every evening,

Blumberg arrived home late,

whereupon he and Norton

settled in front of the TV

with a couple of pizza slices.

0

0

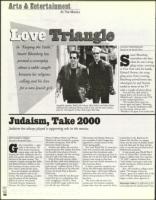

Interfaith relations: Rabbi Jake Schram (Ben Stiller) and Father Brian

Kilkenny Finn (Edward Norton), both in love with the same woman,

play the "God Squad" of New York's Upper West Side.

Over and over, they stared at

Raging Bull or the British cult film

Withnail and I playing on the VCR

in their modest apartment.

"We watched those same two

movies again and again," Blumberg

recalls. "It was like meditation while

we were eating. And we said,

`Wouldn't it be great if we could make

Judaism, Take 2000

Judaism has always played a supporting role in the movies.

a

BENYAMIN COHEN

Special to the Jewish News

od is everywhere — espe-

cially in the movies. His

most recent incarnation

comes today with the film

Keeping the Faith, telling the tale of a

rabbi and a priest who duke it out for

the love of the same woman. The

romantic comedy, starring Ben Stiller

and Edward Norton, follows in the

holy footsteps of many movies that

have tried- to tackle Jewish issues.

Since the inception of celluloid,

Judaism has played a role in the

movies. Not too surprising, consider-

ing that almost all the founding

fathers of cinema were Jewish.

Universal Pictures, Paramount

Pictures, Fox Film Corporation,

.4/14

2000

98

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Warner

Brothers all were founded by a group

of Jewish immigrants, fresh off the

boat from Eastern Europe.

Scholars who follow the way Jews

are portrayed in film explain that there

are basically three phases of Jewish

portrayal in cinema, the first covering

the first half of the 20th century.

Most of the early movies, which

were all silent, dealt with Judaism in a

way that "could appeal to any immi-

grant group," explains Sharon P. Rivo,

the executive director of the National

Center for Jewish Film at Brandeis

University.

Early films made by non-Jews por-

trayed the Jew as a sympathetic char-

acter struggling in America. There

were wonderful images made by Jews

as well, she says. Films like

Humoresque and Hungry Hearts are

two examples of silent images that

appealed to a broad section of the

movie-going public.

But, until World War II, most Jews

who were involved with mainstream

culture put their Jewishness aside,

sometimes even running away from it.

Many Jews in the first half of the 20th

century were trying to shed their

Jewish roots and retrofit themselves to

the American dream.

A classic cinematic example is one

of the first full-length talking films,

The Jazz Singer, which had a different

resolution than some of the earlier

silent works produced in New York,

says Rivo.

The movie tells the story of a

young man who became a popular

singer rather than the cantor his father

wanted him to be. Based on Al

Jolson's life, the film, in a deeper

sense, was the story of children break-

ing with their past for fame and for-

tune. It was the story of almost all of

Hollywood's patriarchs.

In the second, post-World War II

wave of "Jewish film", Jewish artists

began to address their own concerns.

"In 1960," explains Professor Rivo,

"with Exodus, you've got a real, won-

derful coming out of Jews proud of

the new Israeli."

Rivo, who teaches a college course

called "The Images of Jews on

Screen," goes on to explain that in the-

mid-1970s the federal government

began to allow ethnic agencies to

Benyamin Cohen is a sta writer at our

sister publication the Atlanta Jewish Times.