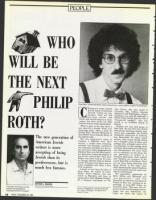

PEOPLE

WHO

WILL BE

THE NEXT

PHILIP

ROTH?

The new generation of

American Jewish

writers is more

accepting of being

Jewish than its

predecessors, but is

much less famous.

Steve Stern: "Living in the South, it never occurred to me I had a tradition on which I could fall back."

ontrary to rumor, reports

of the death of American

Jewish writing are pre-

mature. Jews are still

writing stories and

novels with Jewish themes or inspi-

rations, but their works are often

undiscovered or under-appreciated.

What is gone is the day when a

new opus by a Jewish writer was

front-page news, when a book by

Phillip Roth, Bernard Malamud or

Saul Bellow was a Literary Event of

the highest order.

The new generation's vision of

Judaism is different from their

seniors' — maybe more accepting,

certainly less ferocious, sometimes

less informed. And they are less ur-

ban and more widely geographically

dispersed than was the older genera-

tion that often lived in the shadow of

the Jewish world of New York. Saul

Bellow may have lived as far away

as Chicago, Herbert Gold as distant

as San Francisco, but theirs was an

urban sensibility and, often, a New

York sensibility.

Instead, we now have the likes of

Steve Stern, 42, author of Lazar

Malkin Enters Heaven, who was

raised in Memphis and lives in

upstate New York; Michael Chabon,

27, a frequent contributor to The

C

ARTHUR J. MAGIDA

Philip Roth: Did he throw out "the

baby with the bath water by

separating himself from the past?"

48

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 1990

Special to The Jewish News

Arthur J. Magida is a senior writer for

our sister newspaper, the Baltimore

Jewish Times.

New Yorker, who was raised in

Columbia, Md., halfway between

Baltimore and Washington; Allegra

Goodman, now only 23 (although a

fellow writer joshed that she was a

"12-year-old prodigy"), who was

raised in an Orthodox family in

Hawaii.

Because the lure and power of

New York, the city that once almost

defined the American Jewish expe-

rience and, especially, the Jewish

immigrant experience in America,

has diminished for these newer

writers, more recent Jewish fiction

has a broadei sense of place and,

perhaps also, a broader sense of be-

ing American. In this writing, there

are fewer skyscrapers and alleyways

and delicatessens. For sure, there

are no automats. In one sense, the

new generation of writers is a

Diaspora generation: their accents

and rhythms are innocent of the

Lower East Side or the Bronx. They

are out there being American and

being Jewish at the same time,

often, balancing the cusp of tradition

and assimilation and not quite sure

where it will all lead.

The generation epitomized by

Roth, Bellow and Malamud was

"pre-pluralistic," said Ted

Solataroff, an editorial consultant at

Harper & Row now working on an

anthology of post-1967 fiction by

American Jews. "But now, the ex-

oticism of the Jewish background no

longer has any dominance. No

longer are there the issues of