Wednesday, March 8, 2017 // The Statement

4B

Wednesday, March 8, 2017 // The Statement

5B

Cassandra’s Song

memories from motor city

b y M e r i n M c D i v i t t, Daily Arts Writer

S

pringfield Street, a short stretch of

asphalt on Detroit’s east side, used to

have so many elm trees shading the

road that Detroiters could barely see the sky as

they drove on their way to the freeway. Passersby

would stop for gas after work at Cliff’s, or grab a

snack for the road at the Bamboo Bar, and I imag-

ine they’d stand there for a minute and watch the

husky flecks of sun come down from the west and

nearly stop cold over that dense canopy. In the

summer, when the leaves got thick and bristly,

the trees gave shade to kids biking and roller-

skating down the pavement. The street sweep-

ers would trim the branches so they stayed neat,

twined together so it seemed like one long arch: a

shadowy green tunnel with light at the end.

The trees were the first thing Cassandra

Compton noticed when her family moved to

Springfield from the north side.

“I can remember December 1954 like it was

yesterday,” she said, recalling all the stories she’s

told me.

To me, she’s always been Dr. Montgomery,

never Mel or Cassandra or even a Compton: a

kind recreation director with a Ph.D. in medical

anthropology. She became the director of Del-

ray Recreation Center on the southwest side of

Detroit the year after I began working there as a

high school volunteer. I quickly got to know and

love Dr. Montgomery as we worked side by side

over the years. She cut her hair short last year,

for the first time in a decade, and now it twists

around her head like a halo. Dr. Montgomery is

one of the smartest people I know, and one of the

most caring. Her face is smooth and bright for her

66 years — wrinkle-free, except for a few smile

lines around her eyes and mouth, and a line of

worry stretched thin across her forehead.

While I was volunteering under her, she pep-

pered our conversation with old anecdotes, and

brought her childhood home back to life.

The city’s present state is all I’ve ever known

of it, and I love it as it is. In the five years I worked

at the community center, I met enough wonder-

ful people to pull me back there often, for Christ-

mas parties and baptisms and the occasional

quinceañera.

But Dr. Montgomery’s love is so much stron-

ger and more beautiful. It’s not easy to love a

place when you remember the light glinting at

the western edge of that green tunnel of trees

above 5572 Springfield St., and she tells me you

can’t bring yourself to drive by all that emptiness

where you played, and learned to read and went

on your first date. You can hold it in your hand

and squeeze tightly, but it will just fall through

like dust. I want to understand, at least a little bit,

what it means to love something like that.

******

Detroit, the birthplace of the automotive

industry and the heart of the American Arsenal

of Democracy, hit a golden age coming off the

second World War. Its population hit its all-time

peak of 1.85 million in the 1950s, and the Big

Three automakers — General Motors, Ford and

Chrysler — fueled a growing middle class. How-

ever, labor disputes and racial tensions between

white and Black workers — followed by energy

crises, automation and imports — hurt employ-

ment in the region’s largest industry.

The city would also suffer from severe racial

tensions that came to a head in the summer of

1967 race riots, a product of segregation, unem-

ployment and police brutality. It has been 62

Decembers since Montgomery’s move to the east

side.

“I am 66 years old,” she said. “Let’s put it that

way, and you do the math.”

November 1954 had been cold and clear, sur-

prisingly sunny for a gray Detroit winter. But

December made up for it with piles of thick wet

snow, and while it must have turned instantly to

lead-laced gasoline slush on the gray street below,

up high in the elm trees it would’ve made a tun-

nel all the same, lacier and more delicate than the

jungly summer canopy. On the days that hovered

just above freezing, maybe it looked like a watery

spider’s web, one that would splatter you with

chilly droplets when you walked underneath.

That was their new street, and even with the

novelty of the tree tunnel, Cassandra and her

older sister, Tywania, were not thrilled when

Jimmy Compton Sr. packed up the family that

December and moved across town to Springfield

Street. Their dad worked for the Detroit Post

Office, and he decided it was time for a differ-

ent zip code. To make things even more difficult,

they were the first Black family to move onto the

street.

They missed their old brownstone, with bed-

rooms all upstairs; many years later they would

recognize an almost identical home in the

Huxtable’s apartment in “The Cosby Show,” and

remember it fondly. They got used to their new

house on Springfield Street, though, and the way

she talks about her former neighborhood often

makes me wish I had grown up there.

Cassandra was 4 then, but already everybody

called her Mel. Her middle name is Melody, and

the nickname stuck. She used to sing with her

brothers and sisters while her mother played the

piano.

“It rained 40 days, and it rained 40 nights;

there wasn’t no land nowhere in sight. God took

a raven to bring the news, hoisted his wings and

away he flew. To the East! To the West!”

Mel’s sister would stand behind her and har-

monize, “Didn’t it fall, my Lord, didn’t it rain!”

Mel still sings, in church concerts and on her

own, and sometimes to me. Her rich voice fills

the room, even if we are in the high-ceilinged

gym of the community center. She hums melo-

dies that have stuck in her mind long after her

nickname slid off, songs that sweep me up in her

nostalgia for a different time.

“It seemed like everything we wanted was

close by, you know?” Mel said, her voice bright

when describing her childhood home. “Big stores

— there were still mom and pop stores. We could

walk within a mile radius — I could go roller-

skating; to a restaurant; I could do Christmas

shopping; I could get donuts from the bakery; I

could go to the movies; I could go swimming.”

These are things she can’t do now because many

of these businesses are now shuttered and the old

residents now departed.

Dr. Montgomery talks about this time and

place with such longing. The snow heaps up

outside the coffee shop and I can close my eyes

and see Springfield in summer: Head east out

the front porch, turn right on Shoemaker Street

and pass Betty’s Sweet Shop, with model cars (all

American, of course) and candy and a chrome-

plated soda fountain just like in the movies.

Round the corner again at Lemay, and there’s

Rinaldi’s Supermarket. Frank’s was across the

street, and a restaurant with jukeboxes and cheap

hamburgers, and those plush stools that kids can

swirl around on until they start to feel sick.

Turn back for home and there on the corner

of Shoemaker and Springfield was a big empty

lot with some old billboards. “It was kind of hilly,

and you’d play in the ice and the snow, or in the

summer we went and would catch grasshop-

pers — you can’t get me to go in tall grass now,”

Dr. Montgomery remembered with a chuckle “I

don’t know how I did it back then. I was a kid. I

was a tomboy.”

*****

Dr. Montgomery isn’t the only one grasping

at these old memories. So many of the people

who live or work in Detroit today, and those who

were raised in the city but moved away — Dr.

Montgomery now lives mere miles from me in

Washtenaw County — are nostalgically drawn

to the glimmer of the old city, the splendor of

its ballrooms and mansions and movie palaces.

Publishers can’t print enough books with titles

such as: “Detroit: An American Autopsy,” “Hid-

den History of Detroit,” “Once in a Great City,”

“Detroit City is the Place to Be,” and “Where Did

Our Love Go?” There are more than 1,000 images

tagged “Detroit Nostalgia” on Pinterest, entire

Tumblr blogs and coffee table books and art-

ists’ careers dedicated to frayed black-and-white

photographs. In them, older suburbanites lament

their lost childhood homes and recite the litany

of forgotten city landmarks like well-worn rosary

beads, like saying them over and again will bring

them back to life: Hudson’s Department Store,

the streetcar, Vernor’s Soda Fountain.

Even Berry Gordy, Motor City’s prodigal son,

returned to cash in on this thirst for nostalgia.

Two years ago, I took the University of Michigan

shuttle to see “Motown: The Musical,” Gordy’s

version of the record label’s rise, from Hitsville,

U.S.A. to Hollywood. This was the nostalgic nar-

rative, Motown the company as gentle and pater-

nal, Motown the city as idyllic until the riots hit.

I lapped it up. Gordy crammed the musical with

every classic hit he still held the rights to, and,

sitting there in the Fisher Theatre, surrounded

by older ladies jamming to every song like it was

1965, I beamed for three hours straight.

It was nothing, though, compared to what the

Comptons saw at the Motown Revues. Forget

plain old nostalgia. If I too had been able to see

The Jackson 5 and The Temptations in the same

night — as Mel was able to multiple times while

growing up — I’d be clawing at the door of the

Fox Theatre like it was a time machine, begging

to go back. In the 1960s, Motown would toss all

its artists into one big show around Christmas-

time. They would perform maybe four shows

a day, one after the other, with a short break in

between. Mel would stay for all of them.

“We got there in the morning, and they didn’t

clear out the Fox and say, ‘Hey, you paid for this

time, for another group.’ You could stay. (Their

wait brought them) Gladys Knight and the Pips,

Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and Tammi,” Mel

said, drawing out their names long and slow.

“Tammi Terrell was beautiful. Those big pretty

eyes, and the way she wore her bangs — they kind

of had a little peak right there. Oh, she was beau-

tiful.”

Listening to my recording of our conversation,

scratchy voices heard above the saxophone music

of the coffee shop, something in Dr. Montgom-

ery’s tone struck me. I rewound a few seconds,

“Oh, she was beautiful.”

*****

Dr. Montgomery’s stories are all tinged with

this soft quality of light, these infectious melo-

dies that make me want to believe, to go back.

“Sometimes when I’m talking to you, I hear

music,” she tells me. “I’d carry a transistor radio

about as big as a box of cracker jacks. … I’m walk-

ing home listening to Dee Clark singing ‘Rain-

drops.’ ”

That glossy sheen never really wears off Dr.

Montgomery’s memories of this time.

There are nicks in the varnish, though, and

they get bigger as we talk, as each year of Mel’s

childhood passes by with a quick step, as the

grown-up world creeps in alongside the slow and

tedious decline of her neighborhood. Growing up

in the first Black family on a Detroit street was

not all jukeboxes and soda fountains.

“It was challenging,” she said. “Our neighbors

on either side of us were welcoming, but there

were neighbors farther down that weren’t so wel-

coming, and did some things that, you know …

weren’t neighborly.”

The kids made up other nicknames, too, these

ones not particularly fond or funny.

“There was another lady, we called her ‘Miss

Hellcat-Raiser,’ because she didn’t like Blacks,”

Mel remembered. “Neither did her son. I don’t

know where we got that name from.”

Other neighbors ignored Mel, pretending she

didn’t exist and refusing to move their spurting

hose from the sidewalk to let her pass by on bicy-

cles and roller skates. The shade of the canopy

overhead could protect the Compton kids from

the harsh sunlight, but there was little protection

against a petty, agitated white neighborhood — a

neighborhood whose local high school yearbook

was titled “The Aryan” until a year or two before

Mel enrolled there.

Then there was a neighbor who never had a

nickname.

“There was this one gentleman that would not

want to walk on the same side of the street with

us,” Mel said. “And if we did get too close with

him, he’d take the collar of his coat and put it up

to his face, and he’d turn to the side and spit on

the ground.”

And there were faceless neighbors too. Ones

who came in the night and broke all their garage

windows.

As bad as things could get on Springfield

Street, they were nothing compared to the

Compton’s original home: Alabama. Mel was

born in Birmingham, and her grandparents lived

in an old company town built by the steel indus-

try. Though she grew up in Detroit, the Comp-

tons would visit Alabama when they could to

catch up with family. She remembers the view

out the window seat of the Greyhound bus as it

approached the city during the trips throughout

her childhood — first, flat farmland, then, heavy

industry on the outskirts and the hulking, slight-

ly goofy silhouette of the huge steel Vulcan statue

that welcomed them to Birmingham, glowing

dark red while the sun set.

It wasn’t much of a welcome. Grandma Lar-

cena and Grandpa Mose kept the Compton kids

occupied, but as Mel entered her teens, she start-

ed to notice things. She would sit on the stoop in

her red majorette boots, which got so tattered by

her marching that the heels wore off. Just down

the way was a bar.

“To my right when I looked over my shoulder

was ‘Black Only,’ and I looked over my shoulder

to the left and it was ‘White Only,’ ” Mel said,

referring to the Jim Crow-imposed signs on pub-

lic spaces in the South. She was a northern kid

unfamiliar with this sort of legally codified dis-

crimination, so she stared too long and too hard.

“I was looking over there and they stared at me,

like ‘What are you doing?’ ” she remembered.

“And they were hostile.”

By the late 1950s and early ’60s, the memory

fades out.

“It seems like everything after that is blank,”

Dr. Montgomery said. “I don’t know if we took the

bus, or were they boycotting at the time? I don’t

remember, I don’t remember. I just know when

I saw that look on their faces, I can’t remember

anything after that.”

Soon after, the trips faded too. The Compton’s

last visit down to Birmingham was in 1959. After

that, some of the buses that went down stopped

coming back up. The Freedom Riders took the

Greyhound too, from Detroit and other cities in

the North. Mr. Compton didn’t want his children

sitting next to these well-meaning kids who had

no idea what they were getting themselves into.

“My dad was fearful of letting us,” Dr. Mont-

gomery said. “It was bittersweet. I felt a little

resentful that year after year we couldn’t visit

because of the civil unrest.”

One of these buses sits in the Birmingham Civil

Rights Institute now — its hull, that is, charred

and bare. Sometimes, people would set fire to

the Greyhounds as they carried the Freedom

Riders, idealistic students on a mission to regis-

ter Black southerners to vote. Her father didn’t

want his children coming back up north the way

14-year-old Emmett Till did — in an open casket.

Mel’s mother sang for the True Rock Missionary

Baptist Church on the east side; later, the family

switched to the Lemay Avenue Baptist Church.

Plunk these churches down in Birmingham, and

Mel might’ve ended up like Denise McNair. Or

Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins or Cynthia

Wesley. That Birmingham church bombing, the

notorious one in 1963, was the third such incident

in 11 days in the city.

*****

There is a dark side to our nostalgia — the

memories that are hazy and gray, the things that

Mel didn’t understand well at the time and have

since faded, fast. Yearning for the past also means

a shared agreement that we will cast out the rec-

ollections that don’t fit. Or perhaps agree that the

present day is not better, but worse. That what lay

at the end of the tunnel was not salvation.

The glumness of these memories casts a pall

over the warm glow of Springfield Street. Still,

Dr. Montgomery and I sail past them, perhaps

too easily. Recollections are twisted like bal-

loon animals into what we wish to see in them;

words, those nimble acrobats, contort themselves

around tricky subjects.

Consider a memory Dr. Montgomery shared a

little earlier: the thinly veiled racial animus she

received from some of her more distant white

neighbors. Dr. Montgomery paused for a second,

and then she wasn’t Dr. Montgomery anymore.

She was Mel. The gleam of Springfield Street,

of that shining tunnel of tree canopies, would

always win out over the foggy gloom of the bad

days.

“But the trees,” Mel pivoted. “The street

sweepers would come, they’d trim the trees. I

mean, it was just this beautiful archway that it

looked like.”

*****

A Methodist pastor, Woody White, had moved

across from the Comptons on Springfield Street

and took them to church on East Grand Boule-

vard every Sunday. He encouraged the kids to do

service, and Mel started getting involved in the

church group.

“That was the most impactful time of my life

— in the Methodist Youth Fellowship,” Mel said.

“(Reverend White is) a staunch, staunch advo-

cate, to this day, for civil rights.”

On June 23, 1963, he took the Compton kids

to a civil rights march at Cobo Hall down by the

river. Jimmy Sr. was across town representing his

union in the march.

“I have a picture of my dad holding a picket

sign that reads: ‘President Lincoln freed the

slaves, but did nothing for the Negroes. Free us!’

” Mel remembered. “And for a long time, I didn’t

know what that meant.”

This was no ordinary event. At the time, just

a few months before the March on Washington,

it was the biggest civil rights demonstration in

American history. It drew a crowd of 125,000

people. Mel wore her best dress, and craned her

neck to see, and Martin Luther King Jr. walked

up to the podium in Detroit. Organizers called

this the Walk to Freedom; later, King would call

it “one of the most wonderful things that has hap-

pened in America.”

And King said this:

“I have a dream this afternoon that one day,

one day little white children and little Negro chil-

dren will be able to join hands as brothers and sis-

ters. … And with this faith I will go out and carve

a tunnel of hope through the mountain of despair.

With this faith, I will go out with you and trans-

form dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows.”

Later that summer, King would deliver an

abridged version of this speech on the steps of

the Lincoln Memorial, overlooking more than

200,000 people on the National Mall. This, of

course, would eclipse the Detroit march until

it faded into nothing more than a footnote, an

unlikely story told by wet-eyed grandparents.

That September in Detroit, as schoolchildren

prepared to return to class, a bomb detonated

by members of the Ku Klux Klan would kill

four little girls, blind an 11-year-old in her right

eye, and injure 20 others. At the twilight of that

decade, King was shot, riots racked Mack Avenue

and Woodward as Mel took the bus home from

a concert downtown, a war began in Vietnam

and classmates lost their lives, those hostile and

frightened white neighbors moved away and

didn’t come back. The decades passed, and Mel

became Dr. Montgomery and moved away. The

house on Springfield Street was torn down.

I want so badly to believe in just the happy

stories — the snow globe city in Mel’s memories.

I think that’s what Dr. Montgomery wants, too.

She spins her stories around me faster and faster,

it dizzies me and I imagine we pick up the globe

and shake so hard. And the snow turns to leaded

slush and ashes. And we are back in the desert,

wandering; wandering.

This is all I can give you; it’s all I have. Hold

Springfield Street 1963 in your hand and hope it

doesn’t slip through like dust. And there is no five

years later. No slumped, bloodied reverend, no

sun-bleached balcony in Tennessee. No house-

burning, fear-raising riots; no broken windows;

and no concerts cut short by nearby looting. No

for-sale signs or wood-panelled station wag-

ons speeding to the east, to the west. No Devil’s

Night, no flames.

There is none of this.

Instead, Berry Gordy gets King to record some

speeches at the label before the big day. He nearly

jumps out of his socks when the good reverend

instructs Gordy to donate all royalties to the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference. King

doesn’t want a cent. Gordy never forgets.

Instead, Jimmy Compton Sr. gets up early

like usual and marches with the postal workers’

union. In a few years, Jimmy will be president of

the union, bringing him plenty of trouble and a

reputation as a hell-raiser. He will always stand

for what is right, and raise the Compton kids to

do the same. Jimmy steps down the asphalt in his

old work boots and holds his sign aloft, gingerly,

like it doesn’t weigh more than an ounce.

And Mel wears her Sunday best, and strains

to hear the reverend in the echoey hall, and what

she does hear, she likes. Afterward they ride

back home with Woody and Kim White, and pass

under the tunnel of elms, leaves thick and check-

ered with sunlight in the late afternoon. And

maybe on the other side, there is salvation.

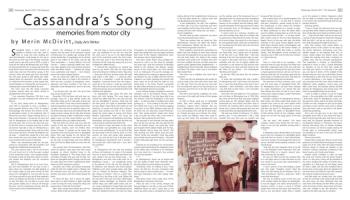

COURTESY OF DR. CASSANDRA MONTGOMERY