Wednesday, October 21, 2015 // The Statement

4C

Wednesday, October 21, 2015 // The Statement

5C

I

n 2012, the downtown Ann Arbor area saw 28 new

businesses.

In 2013, there were 38 more.

By June of 2014, the last time comprehensive data was

released, another 15 new businesses were already planned for

the upcoming year.

Their types varied, from a new outpost of Babo’s Market in

Nickels Arcade to vintage and antique store Thistle and Bess.

Alongside them, new housing developments were popping up

as well, with more than ten apartment and condo complexes

entering or exiting construction over the past few years.

Depending on who you ask, those eighty-four businesses

represent an upwards trend that’s been happening in the area

for the past few years. Or the past ten years. Or the past thirty

years.

Regardless of the timeline, though, the growth is good —

that’s what a number of downtown stakeholders, from the city

to business owners to residents to business associations, all

seem to agree on.

But for many of those same stakeholders, the changing

face of downtown has also prompted concerns about another

trend: the sharply rising cost of living in Ann Arbor, and what

an increasingly prosperous downtown means for the economic

diversity of the city.

Reasons for growth

It’s difficult to point to just one reason why downtown is

seeing change and growth, or how development might correlate

to affluence. The way cities grow and change is complex, and

Ann Arbor is no exception.

Part of understanding what’s happening to Ann Arbor is a

question of looking at national trends on prosperity, according

to City Councilmember Sabra Briere (D–Ward 1), who has been

active in city politics since 1978.

“Affluence is just one part of this, and that goes across the

entire country,” she said. “The gap between income brackets

grows, the people in the middle shrink. And so what that really

means is that a lot of people who twenty years ago were living

comfortable lives in a place like Ann Arbor, earning $40,000 a

year, are confronting the fact that they could not buy a house in

Ann Arbor now.”

When it comes to the specific patterns of business growth and

subsequent affluence, Maura Thomson, director of the Main

Street Area Association, said it’s something a lot of downtowns

are experiencing nationwide, albeit in different ways and forms.

“I am sure you can go to any downtown in America, and see

similar patterns,” Thomson said. “But I think those are the

lucky ones, because I think what you’re going to see in a place

that isn’t maybe as economically vibrant (as Ann Arbor), is

you’re going to see downtowns with stores closing but nobody

filling the space. And we don’t seem to have that problem here.”

Within Ann Arbor, the growth over the past few years seems

to be connected to a multitude of factors, each influencing the

city in a different way, from the type of business on the street to

changes in housing density and average income.

Downtown is frequently divided up into four neighborhoods

— Main Street, Kerrytown, State Street, and South University

areas — for planning purposes, and each is experiencing

changes in a unique way, said Thomson.

“I think you’re going to find a different perspective in each

one of the four neighborhoods,” she said. “This neighborhood,

Main Street area, the student impact isn’t as great as, of course,

South U. and State Street. Each neighborhood is going to have a

little bit different reflection of the changes that are occurring.”

Maggie Ladd, director of the South University Area

Association, agreed that different parts of the city were seeing

different changes.

For the South University and State Street areas, she said

change over the past years has been largely expressed in the

balance of businesses, pointing in particular to a higher number

of retail businesses in the area.

She said she thought the changes had more of a cyclical

nature, as opposed to a push toward affluence — and that the

balance between retail and restaurants could already be self-

correcting in another iteration of change.

“It’s cyclical and I think what you’re seeing on State Street

is more balanced than you’ve seen in the past,” she said. “Their

mix is beginning to be balanced and that’s because I think

you have more people living downtown and you have the IT

businesses going, you have the office workers there so they

create a demand.”

On Main Street, Thomson said, growth has also been

signalled through a shift in the type of business, though in

a different sense, and more definitively in a trend toward

affluence.

“Our downtown is becoming less available to, perhaps,

the mom and pop stores and local business that I think a lot

of people in Ann Arbor were used to,” she said. “So I think

we see a change, as far as the type of businesses that we see

downtown, are catering to the more affluent because they are

businesses that can afford to pay the rent. And in this particular

neighborhood, we have seen in the last years, we have seen huge

turnover in the sale of property, and that’s what drives it.”

Thomson cited several of the same factors Ladd did in

explaining the shifts, pointing to more visitors, Ann Arbor’s

booming technology sector and higher housing density from the

new housing developments as a reason for increased prosperity

in the area.

“I always use cranes as an indicator of a strong economy

and if you go around downtown Ann Arbor and look, currently

you’re seeing some cranes up there,” she said. “And it’s also, with

the increase in residents, we’re also seeing kind of a little bit

of downtown expanding a bit from what we have traditionally

thought of as downtown….residents and employers (have a)

huge impact on our downtown economy.”

Business owners cite a number of reasons why they’ve chosen

to expand over the past years.

Roger Hewitt is a co-owner of Red Hawk Bar & Grille as well

as Revive+Replenish, a higher-end restaurant and grocery store

that opened in the South University area in 2010. He said he and

his business partner felt that opening a business like Replenish

made sense in recent years in part because of a customer base in

the area that could support it.

Speaking to why the downtown area is able to support a

business like Replenish, as opposed to a more wholesale, less

high-end grocery store, he pointed to students and the new

development of high-rises in the area in particular.

“The main thing, if you look at all the student high rises,

they’re fairly expensive places,” he said. “People there have

disposable incomes.”

“I think the student body as a whole probably has more of a

disposable income for groceries than say, the average shopper

at Meijer,” he added.

Nonetheless, Hewitt, who is also the vice chair of the

Downtown Development Authority, said he thought the area

has seen change and prosperity, but not necessarily in the

direction of higher affluence, pointing in particular instead to

a rise in mid-priced dining options.

Consequences of change

What development and growth downtown means for the

city in terms of its economic future is a messy question. Across

the spectrum, stakeholders in downtown are quick to note that

there are both positive and negative aspects.

One thing, though, is clear — it’s expensive to live in Ann

Arbor, much more so than the rest of the state.

Overall, the yearly cost of living in the city for a four-person

family is currently at $68,302, higher than any other region in

Michigan, according to the Economic Policy Institute. And,

according to the 2014 Washtenaw County Housing Needs

Assessment, 31 percent of Washtenaw County residents don’t

make enough to afford a two-bedroom apartment in Ann Arbor,

a figure that includes the median salaries of many jobs located

in the city.

For Thomson, the question of balance between prosperity

downtown and affordability is familiar in a personal light.

“I’m one of the people that I live in a near-downtown

neighborhood, I rent an apartment, that if my rent does go up

I probably won’t be able to stay this close to downtown and I

might not even be able to stay in Ann Arbor,” she said.

“Which makes me — you know, I love Ann Arbor, and I’m

passionate about the job I do, and I think it’s wonderful that

we’re so successful. But it’s hard for people who maybe aren’t

in an income bracket that will allow them to continue to stay as

things continue to increase.”

In a sentiment repeated by many, City Councilmember

Graydon Krapohl (D–Ward 4) said he thinks the development is

good, but that there are unresolved issues downtown, especially

when it comes to housing.

“Any type of growth like that is positive,” Krapohl said. “It

generates tax revenue. It revitalizes areas. I think the challenge

Ann Arbor faces with our housing market is workforce housing,

affordable housing for our workforce. That’s a challenge for us

and part of it is, you know, we don’t have a lot of land to expand

to build a lot more housing so a lot of it is redevelopment, and

redevelopment is expensive.”

Increased housing density — one of the same factors cited

in discussing reasons for growth — and housing prices seems

to have become a particularly noticeable issue as growth has

continued in recent years.

A recent Michigan Daily survey found that locating housing

downtown is currently so competitive for students that many

now sign leases 10 to 12 months in advance. For residents

overall, the County Housing Needs Assessment found that to

keep up with the number of jobs in the city, 3,137 additional

workforce housing units would be needed in Ann Arbor over

the next years.

Workforce housing generally refers to housing that is

affordable for individuals whose income doesn’t currently

allow them to find homes within a reasonable distance to their

workplace, based on the market prices.

When it comes to pricing, there are upward trends for both

housing and rents. According to the Ann Arbor Area Board of

Realtors, in October 2012 the average selling price for a house

was at $216,465. In April of 2015, it was at $269,321. The median

sale price of a home in the United States is currently $225,000

according to Zillow’s housing index.

Rental prices have seen a similar increase, rising by up to 10

percent in the area for 2014-2015, according to MLive, compared

with a national average of 3.6 percent.

“Our downtown is definitely gentrifying,” Thomson

said. “And it’s causing neighborhoods, near downtown

neighborhoods that were at one time affordable to people who,

you know, were maybe working in the restaurants or working

in the shops, it’s becoming so that it isn’t affordable. And I

think that’s something that our city has recognized, affordable

housing is a huge issue.”

High cost of living, of course, isn’t only a one-factor issue.

Briere noted that in Ann Arbor, the income of the population for

both students and residents, as well as the construction that’s

part of new development, also plays a big role.

“The reasons for the higher cost of living and therefore the

sense of increased affluence are complex,” she said. “Some

of it is how much income people get from their jobs. Some of

it is they get that income because the cost of living is so high.

Some of it is we can charge this amount of money for a rental

unit because U of M students have affluent parents. Part of it

is that new construction in the downtown is inevitably going

to be more expensive than older construction. Maybe not

significantly more expensive, but more expensive.”

For some, the biggest factor in regard to cost of living is that

the relationship might be flipped — higher affluence in the area

prompting prosperity downtown, instead of the other way

around.

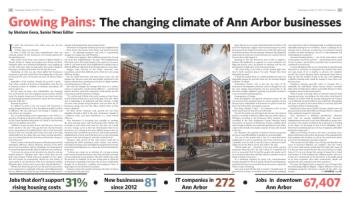

Growing Pains: The changing climate of Ann Arbor businesses

by Shoham Geva, Senior News Editor

New businesses

since 2012

Jobs that don’t support

rising housing costs

IT companies in

Ann Arbor

Jobs in downtown

Ann Arbor

81

31%

272

67,407

LUNA ANNA ARCHEY/Daily

See BUSINESS, Page 8C