PURELY COMMENTARY

8 | JANUARY 5 • 2023

A

lumni and fans

of the University

of Michigan will

do a lot of cheering this

holiday season, whatever

the football team’s fate in

the national playoffs. For a

quasi-interested

observer,

who roots for

another Big Ten

team, it’s rather

easy to mark

when moments

of ecstasy fully

grip the U-M

faithful: they are always

punctuated by the stirring

brass of “Hail to the Victors.”

It’s a great fight song,

maybe the best in college

football, but I had never read

the lyrics before setting out to

write this piece. Yeah, I knew

there were a lot of “hails”

in it, but the song always

seemed opaque, perhaps

caused by the Latinate

construction of the opening

verse: “Hail! to the victors

valiant.” I should also declare

that massive crowds of people

shouting “Hail!” in unison

make me rather uneasy.

But I’m glad to learn finally

the phrase “victors valiant,”

because unlike the song’s

second line, with its emphasis

on conquest — “Hail! to the

conqur’ing heroes”— the first

invites thoughts beyond the

gridiron. Valor may be most

often ascribed to soldiers in

combat, but the word has

wider implications, conveying

in Webster’s terms a “strength

of mind or spirit that enables

a person to encounter danger

with firmness.”

Throughout the six hours

of The U.S. and the Holocaust

Ken Burns and company

brought a host of villains

before us. Hitler, of course,

but also such Americans as

Breckenridge Long, the State

Department obstructionist,

Father Charles Coughlin, the

mad dog radio priest from

Royal Oak, and perhaps worst

of all, Charles Lindbergh, the

famed aviator whose support

for isolationism made him

seem a Nazi dupe, if not an

outright antisemite.

Although I am wary of

attempts to seek optimism

amidst Holocaust despair,

the sentiment too often

ascribed to Anne Frank, a

search for the valiant, those

who confronted Nazi evil

yet remained steadfast, is a

precious part of this history.

The reality of life during

the Nazi terror is that Jews

who survived were, in nearly

all cases, helped by someone,

somewhere, at some crucial

point. And while the Burns

documentary perhaps focuses

a bit too much on what

Americans did not do, it does

include segments on rescuers

like Varian Fry and John

Pehle, though neither man

put himself in harm’s way.

Diplomats, emissaries and

government officials seldom

do.

Which makes the story

of Raoul Wallenberg all the

more inspiring.

His rescue efforts as

a Swedish diplomat, the

subject of many books and

films, brought numerous

posthumous honors. The

street next to the U.S.

Holocaust Memorial

Museum was renamed

Raoul Wallenberg Plaza. A

dozen years

earlier in 1981, Congress

awarded him honorary

American citizenship, only

the second recipient in its

history, joining him with

Winston Churchill. Yet how

many among the 100,000

who fill the Big House on

Saturdays in October could

name this exemplary man

as a University of Michigan

alumnus? Or know that there

is a Wallenberg Endowment

to support University of

Michigan students inspired

by this great humanitarian?

(You can donate via this

link: https://leadersandbest.

umich.edu/find/#!/good/

wallenberg.)

He graduated with honors

in 1935, earning a degree in

architecture. Though from a

wealthy family, Wallenberg

resisted the trappings of

his privilege; indeed, he

chose Michigan over Ivy

League institutions because

of its place as a major public

university. During his years

attending the university, he

lived in modest apartments,

ate breakfast each day at

the Union, and even spent

vacations hitchhiking across

the United States and Mexico.

I would be the last to argue

that a university education

made Wallenberg the person

he became. There were too

many Nazi murderers with

PhDs, MDs, and JDs for me

to ever have complete faith in

higher education’s ennobling

influences. But I’m tempted

to believe that Wallenberg’s

encounter with ordinary

Americans during the

Great Depression, whether

in Ann Arbor or on the

nation’s highways, must have

strengthened the empathy

that was fundamental to his

character.

You can read about Raoul

Wallenberg on your own, or

perhaps watch the 1990 film

Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg,

and learn how in Budapest

he saved at least 4,000 Jews

through a combination of

courage and what can only

be termed chutzpah. With

almost no authority to do so,

Wallenberg issued thousands

of official looking papers that

declared the holders under

the protection of the Swedish

government. He housed these

Jews in apartments that he

then claimed as Swedish

territory.

Rob

Franciosi

guest column

A ‘Victor Valiant’

continued on page 9

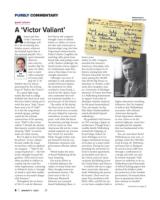

COURTESY OF WALLENBERG CENTER SITE AT U OF M.

Wallenberg’s

student ID card

Raoul

Wallenberg