OUR COMMUNITY

34 | MAY 26 • 2022

I

t looked like any other funer-

al procession, except there

was no hearse and no corpse.

Volunteers in a small convoy of

cars from Congregation Beth

Shalom in Oak Park to Hebrew

Memorial Park in Clinton

Township were carrying old

prayerbooks and other printed

materials containing the name of

God. According to Jewish tradi-

tion, these need to be stored or

buried, not trashed or burned.

Such items, which can include

everything from old, irrepara-

ble Torah scrolls and worn-out

prayer shawls to primers intro-

ducing children to prayer, are

known collectively as shaimos, or

“names.

” The practice of burying

them stems from Deuteronomy

Chapter 2, where the Israelites

are ordered to blot out and

destroy the names of the gods of

the nations they conquer, but not

to treat God in the same way.

“Sacred texts should not be

discarded in the garbage,

” said

Beth Shalom’s spiritual leader,

Rabbi Robert Gamer.

For thousands of years, Jews

have been storing or burying

such materials in spaces that

became known as genizas, from

the Hebrew verb l’g’noze, to stash

or store away.

The renowned Cairo geniza,

discovered in 1896, was a shaft in

an ancient synagogue wall where

all kinds of materials written in

Hebrew were stored. Because of

the dry environment, the items,

dating back to the 1100s, did not

decompose; they proved to be a

historical treasure trove.

Beth Shalom had 103 cartons

of old printed materials, includ-

ing full sets of prayerbooks last

used in the 1980s, benschers

used for the grace after meals,

old library books and texts from

the religious school. Much of

the material had been in the

synagogue’s basement and had

been damaged in the 2014 flood,

but there was also a complete

Talmud in good condition.

Other materials came from con-

gregants and others who lived in

the neighborhood and had heard

about the geniza project.

“We looked at more than

3,000 books to decide what we

could recycle and what had to be

buried,

” Gamer said. “We tried to

give things away, but not much

was taken.

” One reason is that

many Hebrew texts, including

the Talmud, are now available

free online. People don’t need

the physical books as much any-

more, he said.

Some congregations bury

shaimos in a plot on their own

grounds. In Detroit, most such

materials are interred at Hebrew

Memorial Park in Clinton

Township, under the auspices of

the Hebrew Benevolent Society.

Beth Shalom’s executive director,

Shira Shapiro, worked with cem-

etery officials; once they knew

the number of cartons and their

dimensions; cemetery workers

were able to prepare a long,

narrow plot just large enough to

handle the materials.

A dozen synagogue members

joined Gamer and Cantor Sam

Greenbaum in a brief ceremony

in the synagogue’s lobby before

loading the cartons into cars and

unloading the cartons into the

prepared plot.

Burying books is ecologically

responsible, Gamer said. The

books will return to the earth

to enrich the soil, which will be

used to grow trees, which will be

used to make more books.

A Proper Burial

for Holy Books

Beth Shalom buries old books

containing the name of God.

BARBARA LEWIS CONTRIBUTING WRITER

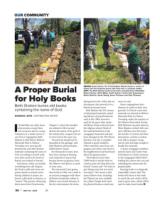

ABOVE: Aryeh Gamer, 15, of Huntington Woods lowers a carton of

books into the prepared grave with help from a cemetary staffer.

LEFT: The Beth Shalom book burial team included (from left) Rabbi

Robert Gamer, Yefim Milter, Aryeh Gamer, Cantor Sam Greenbaum,

Marie Slotnick, Sarah Reisig, Aaron Pickover and Glen Pickover.