rosh hashanah

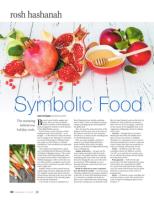

Symbolic Food

STACY GITTLEMAN CONTRIBUTING WRITER

The meaning

behind our

holiday nosh.

82

September 14 • 2017

B

eyond round challot, apples and

honey, there are many symbolic

foods to include in Rosh Hashanah

feasts designed to remind us of the themes

of the High Holiday season.

In fact, there is such a thing as a Rosh

Hashanah seder. Not as formal — or as

lengthy — as the Passover seder, the ritual

has its origins in the Talmud. It is essential-

ly a series of blessings for different foods

and a play on their Hebrew or Yiddish

translations. Each symbolizes the potential

of a new year.

“Any custom involving food is a good

one,” said Rabbi Bentzi Moussia Geisinsky

of Chabad of Bingham Farms. “The words

of the foods of the Rosh Hashanah seder

are closely related either in the Hebrew or

Yiddish language to other words that con-

vey either positive or negative omens and

have served us well from way back when as

well as right now.”

Positive omens revolve around increas-

ing blessings, fortunes, offspring and mitz-

vot. Negative omens stem from centuries

of persecution and ask in the new year that

the plans of enemies of the Jewish people

be cut off and eliminated.

A few foods or tastes to eliminate at a

jn

Rosh Hashanah meal include anything

sour or bitter. There is avoidance of using

vinegar and skipping the horseradish for

the gefilte fish.

Also, because the numerical value of the

Hebrew word for nuts, egot, is the same as

the Hebrew word for sin, chet, Geisinsky

said there is a custom of not including nuts

at a Rosh Hashanah meal.

Here are some examples of foods to

enhance your Rosh Hashanah festive

meals. Details of the seder, including

prayers, can be found at MyJewishLearning.

com or Chabad.org

Apples and honey — the pair are the

most widely associated with the Jewish

new year. The apples for their roundness,

symbolizing the cycle of the year, and the

honey for hoping the new year will match

its sweetness. When dipping, we say a

blessing asking for a good and sweet new

year of renewal.

Head of a fish (or in some communi-

ties, the head of a lamb) — In some cases,

Geisinsky explained, just seeing a symbol is

a mitzvah. At some Rosh Hashanah feasts,

it is customary to display the head of a

fish or even a lamb and recite the blessing

that in the coming year we should be more

like the head (leaders) and less like the tail

( followers). This symbol has evolved for

those who see it as too graphic, which led

to the custom of serving gefilte fish, or for

vegetarians, displaying a head of cabbage

at the meal.

Carrots — Though there is no direct

blessing for this food, the Yiddish trans-

lation, meren, also means to multiply.

Therefore, it is customary to serve carrots

sliced horizontally into circles to represent

coins in hopes that that our prosperity, as

well as our family, will increase in size.

Leeks — In Hebrew, karti, the word

resembles yikartu, the Hebrew word for

“cut off ” as we ask that our enemies may

be cut off from their plans and not includ-

ed in the Book of Life.

Pomegranate — Full of seeds and

sweet juices, this fruit represents the many

mitzvot Jews are commanded to fulfill,

so a prayer here asks that in the coming

year, our merits will increase and our good

deeds be as numerous as the seeds in a

pomegranate.

Dates — In Hebrew, tamar resembles the

word for yitamu, to end. This sweet fruit is

eaten in hopes of ending the plans of our

enemies. •