jews d

in

the

Eye On

Poland

BARBARA LEWIS CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Survivor’s

father comes

alive through

book of

his pre-war

photographs.

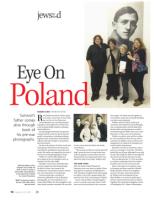

TOP: Ruth Webber and her

daughters Susan, Shelly and

Elaine in front of a photo of

Ruth’s father, Szmuel Muszkies,

at the launch party in Poland

for a book of his photos.

INSET: The Muszkies family in

the late 1930s: Malka, Helen,

Ruth and Szmul.

12

January 12 • 2017

R

uth Webber found her father again

in October, more than 70 years after

she lost him in the Holocaust.

Szmul Muszkies was a professional pho-

tographer in the Polish town of Ostrowiec,

a city of about 80,000 residents, including

about 8,000 Jews.

He photographed portraits and pictures

of important life events for the Jewish and

gentile communities, including weddings,

baptisms, first communions and undoubt-

edly bar mitzvahs, though no such photos

have been found.

He also took pictures of school, social and

trade groups and of the town’s businesses

and industry, including its important steel-

works. His studio was regarded as the best of

the town’s several photographers’ shops.

Webber, 81, of West Bloomfield was

the younger of the two daughters born to

Muszkies and his wife, Malka.

Muszkies’ connections with influential

non-Jews helped save his family, though

he died in Gusen, a sub-camp of the

Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria,

just a few days before it was liberated.

Several months ago, a resident of

Ostrowiec published a book of Muszkies’

photographs, an event marked by a cer-

emony that Webber, her three daughters and

other family members attended. She was able

jn

to learn more about the father she barely

remembered.

“My memories of him are mostly about the

hugs I received when he came home from

work, his genuine concern about my well-

being and the joy I experienced when I was

allowed to play in his studio,” Webber said.

THE WAR YEARS

After the Nazis invaded Poland, the

Ostrowiec Jews were sent to a ghetto. When

their ghetto was going to be liquidated in

1942, Muszkies arranged for his older daugh-

ter, Helen, to live with a gentile family. She

spent the rest of the war passing as Catholic.

He, his wife and their younger daughter

went to a nearby work camp, where condi-

tions were less harsh than in the concentra-

tion camps. The family moved together to

several labor camps, but eventually Muszkies

was taken away separately.

Webber and her mother ended up in

Auschwitz. The infamous Dr. Josef Mengele,

who would determine with the flick of his

thumb which arriving prisoners would be

immediately gassed, didn’t show up to meet

their train, so they were sent to barracks.

Webber was able to stay with her mother

for a few months; but then she was sent to

a barrack for children, many of whom were

designated to be subjects for Mengele’s per-

verted medical experiments.

Her father was also at Auschwitz, and he

sent her a message to meet him. “My father

looked like an old man, although he was only

45 years old, hardly the father I remembered,”

she said. It was the last time she saw him.

She was liberated Jan. 27, 1945, and taken

to a Krakow orphanage where her mother

found her. She was not yet 10 years old.

After a short time in a transition camp

in Germany, and then a period in Munich,

Malka Muszkies and her two daughters

moved to Toronto, where they had fam-

ily. Webber met her husband, the late

Mark Webber, at a survivors’ gathering in

Toronto and moved to his home in Detroit.

Together they raised three daughters, Susan

of Washington, D.C., Elaine of Huntington