Silver Streak

With the largest body of surviving work by a European or American

Jewish silversmith prior to the 19th century, colonial Jewish silversmith

Myer Myers comes to life in book and exhibit.

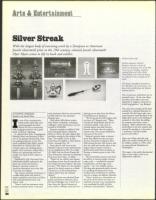

Clockwise from left:

Exhibit organizer David L.

Barquist, associate curator of

American decorative arts at the Kite

University Art Gallery, considers

colonial silvermith Myer *fyers'

Torah finials with intricate decora-

tive details the best examples of his

work.

This bowl, intended to function as

the "slop bowl" of a tea service, is on

loan to the exhibit from the Detroit

Institute of Arts.

This circumcision shield bears the sil-

versmith's name. 'At the time Myers

was alive, silver objects were very

important in religious ceremonies in

Jewish congregations," says Barquist.

SUZANNE CHESSLER

Special to the Jewish News

I

n one of his commentaries,

Maimonides stated that corn-

missioning gold and silver

objects for use in connection

with synagogue services was a good

deed, worthy of a blessing.

In colonial New York, Congregation

Shearith Israel was fortunate to have

one of the greatest silversmiths of the

era crafting works for its use. The

newly published Myer Myers: Jewish

Silversmith in Colonial New York

includes many eye-catching photo-

graphs of his creations, along with a

history of a pioneering artist and

insight into early Jewish culture in

America.

Published by Yale University Press

($60 hardcover/$35 softcover), the

book was written by David L.

Barquist, associate curator of

American decorative arts at the Yale

University Art Gallery.

The volume combines the beauty of

a coffee-table book with hard-to-

obtain material on the history of New

York colonial Jewish history and

Myers' work.

"Myers' work has enormous value

because American silver is rare and

12/7

2001

86

early American silver has not survived

terribly well over the centuries,"

Barquist says.

Only about 400 objects remain

from Myers' workshop, including a

coffeepot, which last January was auc-

tioned for $100,000.

Barquist curated an exhibit of 104

silver and gold objects created by

Myers as well as 50 other objects that

provide a setting for the artistry of the

time. The exhibit will be at Yale

University Art Gallery in New Haven,

Conn., through Dec. 30.

From there it will move to the

Skirball Cultural Center and Museum

in Los Angeles from Feb. 19 to May

26, 2002, and the Henry Francis du

Pont Winterthur Museum in Delaware

from June 20 to Sept. 13, 2002.

"Pieces for the exhibit were chosen

according to how they fit into the sto-

ries being told about Myers," the cura-

tor says. "The objects are not represen-

tative of his shop's output as a whole.

The focus is on the extraordinary

objects rather than the ordinary

objects."

Exhibit pieces were obtained from

public and private collectors, and a

few have Michigan ties. A bowl is on

loan from the Detroit Institute of

Arts, while a coffeepot stand and cov-

ered jug are on loan from the Henry

Ford Museum in Dearborn.

"We borrowed all of the Judaica that

we know of," Barquist says. "These

include the Torah finials and the cir-

cumcision shield. I also tried to

include objects that had histories

because we knew who the original

owners were. The owners themselves

were part of the story."

Barquist's project seeks to demon-

strate that Myers was the most pro-

ductive silversmith working in New

York during the late 18th century and

that his ritual and secular silver is the

largest body of extant work by a

Jewish silversmith from anywhere in

Europe or America prior to the 19th

century.

The silversmith's renown came from

his ability to execute quality custom--

order work — candlesticks, pierced

breadbaskets, covered jugs, cruet

stands — for very wealthy patrons.

His shop also generated steady income

by satisfying the demand for more

modest forms of hollowware and flat-

ware for a larger, less affluent clientele.

"Myers' success as a silversmith was

the result of his talents not only as a

craftsman but also as an entrepreneur

who marshaled the skills of other

craftsmen and specialists," Barquist

The only extant example of this form

marked by a Colonial American sil-

versmith, this dish ring is also a per-

sonal statement made by Myers at the

height of his career as the leading sil-

versmith in New York. By striking

his surname mark twice, writes

Barquist, "Myers claimed this excep-

tional object as his own creation and

asserted his equality, as a Jew and as

a 'mechanic,' with the wealthy

patrons of his labor"

Myers most likely made this soup

ladle with wooden handle for one of

his children, Judith, in 1784, when

she married Jacob Mordechai of

Philadelphia.

This teapot is the earliest documented

object to bear Myers' mark as an

independent craftsman.