FINE ARTS

Remington

STEEL

IS

STEVE HARTZ

Staff Writer

s a child, Henry Rem-

ington dreamed he

would grow up to

become a professional artist.

But his dream would have

to wait 65 years. First, Rem-

ington would have to survive

nightmares.

Born in Austria in 1906,

Remington spent most of his

young adult life working at

his parents' general store

and then selling sports

equipment. At 33, he trav-

eled through Europe,

wishing to receive an infor-

mal education in art. But in-

stead — he was given a for-

mal lesson in life.

"I couldn't get a job," said

Remington, who now lives in

Detroit. "Foreigners, then,

were not allowed to work in

other countries. I was pen-

niless."

To earn money, Remington

purchased and sold fabric

used to make clothing.

"That's how I survived. I

was a salesman."

In 1939, the Nazis invaded

Czechoslovakia, and Rem-

ington was thrown into a

small concentration camp.

Remington and several

other Jews, including a

woman, Greta Grossman,

bribed the Nazis so they

could leave the country.

"We spent 119 days on a

small boat with a Nazi flag

so they wouldn't be

suspicious that Jews were

aboard," said Remington,

who squeezed in the boat

with 710 others. "Occasional-

ly we were sent bread and

water, but for most of the days

we went without food. It was

hell."

Remington finally found

refuge in Israel, where he

married Grossman in 1950.

That year, he moved to

Detroit and was hired by

Ford Motor Company as a

designer. A few months after

he began working at Ford,

Remington caught

pneumonia and was

bedridden for several weeks.

As a result, he lost his job.

"When I got better, I

painted homes and held

various sales jobs — anything

to make a living;' he said.

Twenty years ago, Rem-

ington retired to pursue his

dream.

He first made flowers pots,

magazine racks, picture

frames and tables, using

different kinds of wood such

as ebony and walnut. Rem-

ington also built 70 lamps.

Next, he started working

with copper and sterling

silver, sculpting flowers and

using rocks and drift wood as

their bases. He also sculpted

copper-and-wooden vases.

One of his most precious

pieces of Judaic art is a

copper menorah.

Remington's latest project

is designing earrings,

bracelets, necklaces and

charms. He has made more

than 100 pieces of jewelry.

Because Remington

cannot afford fees charged

by most local art fairs, and

art galleries will not be

responsible for the loss or

damage to his art, he

displays his work at his

home.

His handmade furniture,

jewelry, copper and silver

sculptures and Judaic art

work may be the best kept

secret in town.

Although he's mastered

several art courses and

received various art awards,

Remington said, "God gave

me the talent to sculpt; you

cannot learn this. This takes

a lifetime. You need to have

imagination. Everything I

learned is from my imagina-

tion — not art classes."

❑

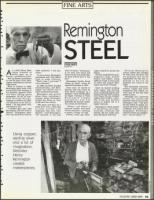

Using copper,

sterling silver

and a lot of

imagination,

Detroiter

Henry

Remington

creates

masterpieces.

THE DETROIT JEWISH NEWS

63