INSIGHT

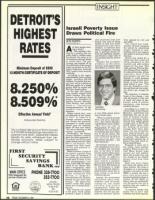

DETROIT'S

HIGHEST

RATES

Minimum Deposit of $500

12 MONTH CERTIFICATE OF DEPOSIT

8.250%

8.509%

Effective Annual Yield*

Compounded Quarterly.

This is a fixed rate account that is insured

to $100,000 by the Savings Association In-

surance Fund (SAIF). Substantial Interest

Penalty for early withdrawal from cer-

tificate accounts. Rates subject to

change without notice.

FIRST

SECURITY

SAVINGS

BANK FSB

MAIN OFFICE

PHONE 338.7700

1760 Telegraph Rd.

(Just South of Orchard Lake)

352.7700

** FederCa%ly Ilured

k

lowit Houswic

OPPORTUNITY

4,

42 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1989

•

.4 ***

/..""

4

HOURS:

MON.-TOURS.

9:30-4:30

FRI.

9:30-6:00

Israeli Poverty Issue

Draws Political Fire

ZE'EV CHAFETS

Israel Correspondent

A

re there people starv-

ing in Israel?

This question, star-

tling for a country that con-

siders itself a welfare state,

has become the center of an

acrimonious national debate

in recent days. The con-

troversy was touched off by

the publication of the annual

report on poverty by the Na-

tional Insurance Institute

(N l), Israel's social security

authority.

According to the report,

approximately half a million

people, including 250,000

children, live below the pov-

erty line, which it defines as

$240 per month for a single

person, $385 for couples and

$615 for a family of four.

In the past, NII reports

have usually elicited little

public interest. This time,

however, the Institute's fin-

dings were attacked by

Deputy Finance Minister

Yossi Beilen, who called

them a "statistical

misrepresentation" of the

country's true economic

situation.

Beilen argued that, since

the definition of the "pover-

ty line" is relative to

average national income,

and income has generally

increased in recent years,

Israel's poor are relatively

better off than ever before.

"No one is starving in this

country," he asserted.

Predictably, the Deputy

Finance Minister's remarks

drew fire from opponents in

the Likud; but he also came

under attack from his Labor

Party colleagues, who

charged him with insen-

sitivity and political ir-

responsibility.

Beilen has been a target of

his party's populist wing

ever since he remarked, a

few months ago, that Israelis

would have to learn to live

with unemployment. Last

week, Labor MK Eli Dayan

called for the Deputy Min-

ister's resignation, while

Shoshana Arbelli Almozlino,

a former Minister of Labor,

acidly commented that

Beilen, a "yuppie,"

misunderstood the situation

because he has never been

hungry. "He apparently

doesn't realize that people

cannot live on bread alone,"

she said.

This criticism was echoed

in the press, which quickly

produced a spate of articles

and interviews with poor

people who told of being

unable to feed and clothe

themselves and their

children. A televised story

about youngsters rummag-

ing in garbage dumps for

food was especially graphic,

and became a major topic of

conversation here for several

days.

Despite the anecdotal

evidence in the press,

however, most experts agree

that Beilen is correct; there

Yossi Beilin:

None starving.

is very little actual starva-

tion in Israel today.

"There is extreme poverty

here, and even malnutri-

tion," says Naomi Shander,

a professional social worker.

"But it's not like in

Bangaledesh. If there are

individuals who are hungry,

it's because they don't know

how to use the system. The

truth is that you can exist on

the services that the

government provides — but

that's about all."

Government services pro-

vide subsistance-level aid to

the disabled and extremely

poor in the form of social

security grants which usual-

ly range from $250 to $400

per month. In addition,

parents with two children or

more receive a monthly

government stipend of about

$25 per child. But because of

an unwillingness to single

out and stigmatize impover-

ished families, Israel has no

food stamp or personal

welfare programs.

Instead, the government

subsidizes basic com-

modities, such as bread,

cooking oil, rice, frozen

chicken and public

transporation. These sub-

sidies, like government child

stipends and old age pen-

sions, are universal, and are

thus enjoyed by rich and

poor alike.

The Likud has tradi-

tionally favored changing

the system by subsidizing

people instead of com-

modities; and it now appears

that Labor is moving in that

direction.

Beilen has called for a

means test that would end

child payments to the

wealthy and add welfare

money for the poor. This

week, his boss, Finance Min-

ister Shimon Peres, implicit-

ly endorsed this idea, telling

reporters that if the

government cut half its

stipends, it would generate

enough money to give every

family in Israel four thou-.

sand dollars a year. "You

can't pay stipends to every-

one and then ask why every-

one doesn't get enough,"he

said.

The existence, in classless

Israel, of two classes — one

well off enough to take care

of itself, the other in des-

perate need of public

assistance —has become

painfully obvious.

According to a study by

Yoram Gabai of the Finance

Ministry, published last

September, the top 10 per-

cent of Israeli income-

earners (excluding money

derived from capital gains)

average close to $4,700 per

month before taxes; while

the bottom 10 percent

average $170. Even after

taxes, the top 10 percent

earn approximately six

times as much as the lowest

10 percent. This disparity,

government analysts say, is

greater than that which ex-

ists in Great Britain.

Proposals to limit aid to

the needy raise another

question: Where to draw the

line? Many Israeli wage

earners are only slightly

above the poverty line, and

any change in the subsidy

system could drop them

below it.

Motti and Aviva Cohen

(not their real names) have

three children. He works in

Jerusalem as a government

chauffeur and earns IS 1300

($650) a month; she has a

part-time government

secretarial job that brings in

another IS 800 ($400). In

theory, they are comfortably

over the poverty line, but in

practice, they are unable to

make ends meet.

"If someone decides that

people like us don't need

subsidies and child stipendS,