SPORTS

T

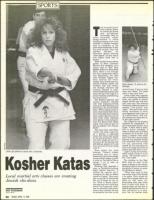

Lezlie Light performs a routine with a chizikunbo.

Kosher Katas

Local martial arts classes are creating

Jewish sho-dans.

MIKE ROSENBAUM

Sports Writer

56

FRIDAY, APRIL 14, 1989

hey are gathering at

local schools, drawn

by a desire for fitness

and self-defense

knowledge. They do

katas (routines), either

empty-handed or while

handling weapons such as sai

(swords) or wooden weapons

such as nunchuku or the

palm-sized chizikunbo. If they

are good enough, they may

achieve sho-dan, an

Okinawan phrase meaning

"first degree." In this case a

first degree black belt in

karate.

These martial arts students

gather at Peter Carbone's

Martial Arts Academy. At a

recent class at West Hills

Middle School in Bloomfield

Hills, which is run through

the city's community educa-

tion department, two Jews

with sho-dans helped Car-

bone instruct the twice-

weekly class. Jewish and non-

Jewish students, adults and

children, men and women,

ran through exercises and

routines, dressed in tradi-

tional barefooted martial arts

style, bowing with respect to

sensei Carbone and following

his instructions.

The Eastern physical and

mental discipline blended

well with American-Jewish

culture for Bob Feinberg and

Steve Kass, the Jewish black

belts. While taking pride in

their achievments they dwell-

ed on what they have and can

learn, rather than the color of

their belts. Their attitudes

were similar to the instructor

from The Karate Kid. When

asked what kind of belt he

had, he replied, "J.C. Penney,

$3.95."

The black belt, says Kass,

"never was really a goal un-

til I became a high-rank

brown belt where that would

be the next promotion. That's

not why I really got into it: I

got into it for the exercise and

self-defense aspects of it and

that just kind of came along

with it."

Kass enjoys the class

because "there's always

something new to learn.

Sensei has a lot of knowledge

stored and he's happy to share

it with us. I'm kind of like a

sponge. I try to soak up

whatever I can."

Feinberg first attended a

class at Southfield-Lathrup

High School because "I

wanted the exercise and I

wanted to be able to defend

myself or friends:' Nine years

ago, at age 26, he discovered

how out of shape he was. In

his "third or fourth class I

was sparring with a little kid,

about 8 or 9 years old. And I

was out of breath after about

three or four minutes. He was

so excited he ran over to his

Scott Leibovitz, 13, works on his

technique.

dad and says, 'I beat up that

man over there.' I've come

quite a way since then."

Lezlie Light had a specific

goal of learning self-defense

when she looked at several

karate schools one and one-

half years ago. She selected

Carbone's classes because he

teaches "vital points," says

Light. "You don't have to be

strong musclemen to down

your opponent and to get out

of a bad situation. Just sim-

ple touches are what does it,

in the right points."

The classes do not prepare

students for competition. "I

don't want sport karate," says

Light. "I don't want to learn

how to punch somebody. I

want to learn how to knock

somebody out if need be. And

being a woman with small

kids, I feel like a prime target

because any attacker knows

I'm concerned with my kids;

I'm not concerned with

myself. So I'm easy. But you

have to be ready and I have to

protect my kids from it, too."

Light's 5-year-old son Sean

takes a class. Corey, 3, is too

young. "He imitates quite a

bit," says Light.

The children in the West

Hills class do most of the

same routines as the adults.

Feinberg believes the mental

discipline of karate is easier

for children to absorb.

"When they come in they

can accept a lot of the things

a lot easier. Their minds are

more like a sponge that's not

filled up with water yet.

Everything that they learn

kind of stays with them. It

teaches them not just how to

defend themselves and how to

have self-control in a situa-

tion, but he teaches them